- Η Ακαδημία

- Ίδρυση

- Μέλη

- Μέγαρο

- Οργάνωση

- Διοίκηση - Υπηρεσίες

- Διοίκηση

- Διεύθυνση Διοικητικών Υπηρεσιών

- Διεύθυνση Οικονομικών Υπηρεσιών

- Διεύθυνση Διαχείρισης Κληροδοτημάτων

- Διεύθυνση Περιουσίας

- Διεύθυνση Βιβλιοθήκης

- Αυτοτελές Τμήμα Εκδόσεως Δημοσιευμάτων

- Αυτοτελές Τμήμα Τεχνικών Υπηρεσιών

- Αυτοτελές Γραφείο Δημοσίων Σχέσεων, Εθιμοτυπίας και Πολιτιστικών Εκδηλώσεων

- Αυτοτελές Γραφείο Μηχανογραφήσεως - Πληροφορικής

- Κανονισμός

- Ευεργέτες- Δωρητές -Αθλοθέτες

- Εποπτευόμενα Ιδρύματα

- Διεθνείς Ενώσεις

- Επιτροπή Ισότητας των Φύλων

- Έρευνα

- Ερευνητικά Κέντρα

- Κέντρο Ερεύνης των Νεοελληνικών Διαλέκτων και Ιδιωμάτων Ι.Λ.Ν.Ε

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Ελληνικής Λαογραφίας

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης του Μεσαιωνικού και Νέου Ελληνισμού

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Ιστορίας του Ελληνικού Δικαίου

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Ιστορίας του Νεωτέρου Ελληνισμού

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Ελληνικής και Λατινικής Γραμματείας

- Κέντρο Ερευνών Αστρονομίας και Εφηρμοσμένων Μαθηματικών

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Ελληνικής Φιλοσοφίας

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης Επιστημονικών Όρων και Νεολογισμών

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης Φυσικής της Ατμοσφαίρας και Κλιματολογίας

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Αρχαιότητος

- Κέντρον Ερεύνης της Ελληνικής Κοινωνίας

- Κέντρο Έρευνας της Βυζαντινής και Μεταβυζαντινής Τέχνης

- Κέντρο Ερευνών Θεωρητικών και Εφηρμοσμένων Μαθηματικών

- Κέντρο Διαστημικής Έρευνας και Τεχνολογίας

- Κέντρο Έρευνας και Εκπαίδευσης στη Δημόσια Υγεία

- Ερευνητικά Γραφεία

- Ερευνητικά Προγράμματα

- Ερευνητικές Υποδομές

- Επιτροπή Ερευνών

- Επιστημονικό Συμβούλιο (Ε.Σ.Ε.Κ.Α.Α)

- Ερευνητικά Κέντρα

- Δημοσιεύματα

- Έντυπα

- Πρακτικά

- Επετηρίδες

- Μνημεία της Ελληνικής Ιστορίας

- Ελληνική βιβλιοθήκη

- Διάφορες εκδόσεις

- Δημοσιεύματα Κέντρων και Γραφείων Ερευνών

- Εκδόσεις του Ιδρύματος Κώστα και Ελένης Ουράνη

- Εκδόσεις της Επιτροπής Ερευνών

- Εκδόσεις υπό την Αιγίδα της Διεθνούς Ενώσεως Κλασικής Αρχαιολογίας και της Διεθνούς Ενώσεως Ακαδημιών

- Ηλεκτρονικά

- Το Βιβλιοπωλείο της Ακαδημίας Αθηνών

- Έντυπα

- Βραβεία

- Υποτροφίες

- Βιβλιοθήκη

- Ανακοινώσεις

- Ψηφιακή Ακαδημία

Σεμινάριο ΚΕΕΛΓ Ακαδημίας Αθηνών 2021-2022

Seminar of the Research Centre for Greek & Latin Literature of the Academy of Athens 2021-2022

Megaron of the Academy of Athens, East hall, 5-7pm (Greek time)

Scientific Coordinator: Έφη Παπαδόδημα

1. Freedom and Unfreedom in the Ancient World

2. Ethnicity, Race, and (the) Classics

** The modalities of each talk will be announced in due time.

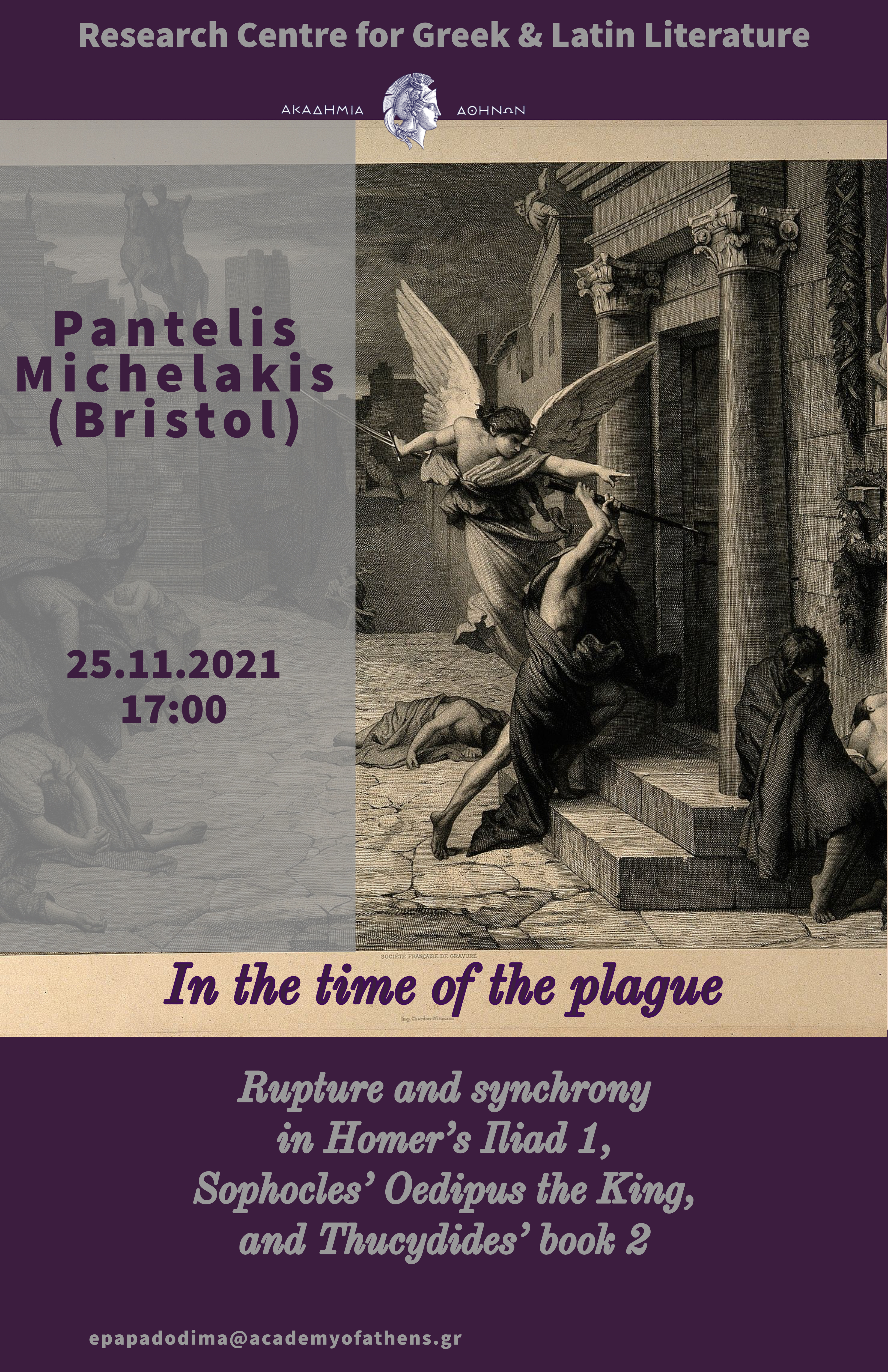

Special lecture: November 25, 2021 (Thurs): Pantelis Michelakis (Reader in Classics, University of Bristol)

In the Time of the Plague: Rupture and Synchrony in Iliad 1, Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, and Thucydides’ Book 2

Abstract

Plagues disrupt the continuity of time but also time as a social good. Victims, witnesses, and aspiring saviours, do not only run of out of time, but they are also unable to coordinate with one another. Plagues, however, also impose a shared experience with its own temporal logic and the urgent need to respond to it. As such, they bring about disruption, while also forcefully relating to one another different times, not least through temporal loops of prospection and retrospection that engulf listeners, spectators and readers. This paper has two aims: to investigate how temporal struggles are dramatized in three of the earliest and best-known plague narratives of archaic and classical Greece and also to examine how cultural techniques of synchronisation are practiced by their characters as responses to those struggles.

1. Freedom and Unfreedom in the Ancient World

The section “Freedom and Unfreedom in the Ancient World” aims to explore various forms of freedom and unfreedom in ancient literature, such as: the institution of slavery; its relation to democracy; the oppression of women and foreigners; and, no less, broader issues of legality, legitimacy, and domination.

Programme

November 11, 2021 (Thurs): Elias Arnaoutoglou (Director of Research, Research Centre for the History of Greek Law, Academy of Athens)

Δουλεία και Δίκαιο. Η περίπτωση της απελευθέρωσης των δούλων

Abstract

Η παρουσίαση μου στα πλαίσια του σεμιναρίου «Ελευθερία και ανελευθερία» θα εστιάσει σε μια μορφή ανελευθερίας, της οποίας σημειωτέον οι μορφές δεν περιορίζονται στη δουλεία ως εμπόρευμα αλλά περιλαμβάνουν την υποδούλωση για χρέη, την εἰλωτεία και διάφορες μορφές δουλοπαροικίας. Ο συσχετισμός δουλείας και δικαίου στις αρχαιογνωστικές επιστήμες υπήρχε από την αυγή της νεωτερικής περιόδου, καθώς είχε εμπλακεί στη διαμάχη για την κατάργηση της δουλείας. Οι δύο όροι του ζεύγους, δούλοι και κανόνες δικαίου, γίνονται συχνά αντιληπτά ως εργαλεία. Αλλά το θεμελιώδες, κοινό χαρακτηριστικό αυτών των φαινομενικώς ασχέτων και ασύνδετων μεταξύ τους εννοιών, είναι η απόλυτη εξουσίαση και ιδιαιτέρως η πιθανότητα άσκησης φυσικής βίας. Δεν είναι υποχρεωτικό ούτε απαραίτητο να ασκείται η φυσική βία, αρκεί η απειλή της. Χαρακτηριστικό παράδειγμα η αποστροφή του δούλου Γάστρωνα προς την Βίτιννα την ιδιοκτήτρια του, στον πέμπτο Μιμίαμβο του Ηρώνδα με τον τίτλο Ζηλότυπος, στ. 6-7: προφάσις πᾶσαν ἡμέραν ἕλκεις, Βίτιννα, δοῦλός εἰμι, χρῶ ὅ τι βούλει <μοι> καὶ μὴ τὸ μευ αἷμα νύκτα κἡμέρην πῖνε (Προφάσεις βρίσκεις όλη μέρα Βίτιννα, σαν είμαι δούλος σου, κάνε με πως επιθυμείς, μα το αίμα μου μην πίνεις νύχτα μέρα - μετ. Μανδηλαράς, Β. Γ. (1986) Οι μίμοι του Ηρώνδα, Αθήνα). Ο δούλος με αυτήν την φράση του αντανακλά τα όρια στη σχέση κυριαρχίας μεταξύ δεσπότη και δούλου. Παραδέχεται ότι πρόκειται για σχέση εκμετάλλευσης και εξουσίασης, αλλά αυτή δεν θα πρέπει να υπερβαίνει τα εσκαμμένα, ποια είναι αυτά επαφίεται στις προσλαμβάνουσες των θεατών και αναγνωστών. Ο δούλος, όμως, είναι ένα δρων υποκείμενο, ακόμα και αν η αριστοτελική θεώρηση επιδιώκει να το συγκαλύψει. Ο δούλος διαθέτει βούληση, νοητικές ικανότητες διάκρισης, επιλογής, αναγωγής και επαγωγής. Μπορεί να διακρίνει και να αποφασίσει εάν, πότε και πως θα συμμορφωθεί ή θα παραβιάσει κάποια κανονιστική διάταξη ή τις εντολές του δεσπότη του. Επομένως, η αριστοτέλεια θεώρηση του δούλου ως ἐμψύχου ὀργάνου/κτήματος αντανακλά την θεμελιώδη αντίφαση που συνιστά η ύπαρξη δούλων στις αρχαιοελληνικές πόλεις. Στη σχετική πρόσφατη πλούσια όσο και ποικίλου προβληματισμού βιβλιογραφία, κυριαρχούν δύο προσεγγίσεις, εκείνη που θεωρεί την δουλεία ως σχέση ιδιοκτησίας, η οποία φαίνεται να κυριαρχεί τις τελευταίες δεκαετίες και η πιο πρόσφατη θέση ότι η δουλεία είναι και μια σχέση «κοινωνίας» όπου η ασύμμετρη κοινωνική θέση των συμμετεχόντων δημιουργεί σχέσεις εξουσίασης. Η απελευθέρωση των δούλων αποτελεί μια κομβική στιγμή στην προσωπική ιστορία τους, διότι αφενός μεν (ανα)γεννώνται κοινωνικώς, αφετέρου αποκτούν μία κοινωνική θέση στο κοινωνικό συνεχές της πόλεως. Η διαδικασία της απελευθερώσεως όπως αναδεικνύεται στις πολυάριθμες πράξεις απελευθέρωσης από την Κεντρική Ελλάδα (κυρίως Δελφούς) και από την Κω (εξαιρώ την Θεσσαλία και την Ήπειρο όπου οι πληροφορίες στηρίζονται σε περιληπτικές καταγραφές, την κλασική Αθήνα των προβληματικών «ἐξελευθερικῶν φιαλῶν» και την ελληνιστική και ρωμαϊκή Μακεδονία λόγω έλλειψης χρόνου) παρέχει μεν πλήθος πληροφοριών σχετικά με τη διαδικασία και τη νομική διάσταση της πράξης, αλλά έχει οδηγήσει στη διατύπωση ριζικά αντίθετων προσεγγίσεων σχετικά με το καθεστώς του απελευθερωθέντος υπό παραμονή δούλου. Πρόσφατα ο Joshua Sosin επανήλθε στο ζέον ερώτημα και με μια αιρετική διάθεση, ερμήνευσε την θέση του υπό παραμονή απελεύθερου ως δούλου. Θα υποστηρίξω την παραδοσιακή άποψη με μια μικρή τροποποίηση, ο απελεύθερος υπό παραμονή δεν ήταν πλήρως ελεύθερος, απολάμβανε μιας «βεβαρυμένης», προς όφελος του πρώην δεσπότη του και μόνο, ελευθερίας. Θα μπορούσε κάποιος να παρομοιάσει την κατάσταση του με εκείνη του κληρονόμου που πρέπει να εκτελέσει πρώτα τις κληροδοσίες που επέβαλε ο θανών για να απολαύσει την κληρονομία του.

January 27, 2022 (Thurs): Charilaos Platanakis (Assistant Professor in Political Theory, University of Athens)

Σωκρατική ελευθερία και πολιτική υπακοή

Abstract

Η άρνηση του Σωκράτη να αποδράσει συχνά ερμηνεύεται ως ισχυρή θέση για την πολιτική υπακοή και ο πλατωνικός Κρίτων φαίνεται να μας οδηγεί σε αυτό το συμπέρασμα. Αυτή η ερμηνεία, όμως, φαίνεται να παραβλέπει ότι ο ίδιος ο Σωκράτης δύο φορές προέβη σε πολιτική ανυπακοή, τόσο σε τυραννικό (η άρνηση της σύλληψης του Λέοντα) όσο και σε δημοκρατικό πλαίσιο (η παρακώλυση της καταδίκης των στρατηγών των Αργινουσών), ενώ στην Απολογία δηλώνει ξεκάθαρα ότι δεν θα διστάσει να παρακούσει την πόλη του αν αυτή του ζητήσει να σταματήσει να φιλοσοφεί. Στην ομιλία μου θα προσπαθήσω να παρουσιάσω τον Σωκράτη ως αντιρρησία συνείδησης για την ηθική υποχρέωση του μη αδικείν και του φιλοσοφείν υποσκάπτοντας τα επιχειρήματα των Νόμων στον Κρίτωνα για την απόλυτη υποχρέωση πολιτικής υπακοής.

March 10, 2022 (Thurs): Mirko Canevaro (Professor of Greek History, University of Edinburgh)

Recognition, Imbalances of Power and Moral Agency: Honour Relations and Slaves’ Claims vis-à-vis Their Masters

Abstract

This talk is concerned with the problem of whether slaves have ‘honour’ – whether they are, that is, implicated in reciprocal relations of mutual respect and recognition, and can develop through these an autonomous subjectivity. It tackles this issue from the vantage point of much recent work in moral and political philosophy, as well as in social psychology – by Charles Taylor, Stephen Darwall, Kwame Anthony Appiah and particularly Axel Honneth – about value, dignity and recognition, and it does so by turning to what is perhaps the least promising kind of social relation, if we are looking for reciprocally empowering honour dynamics; yet at the same time to what is arguably the most fundamental kind of relation for slaves, foundational of their very status and identity as slaves: the relation with their masters. We have plenty of evidence that day-to-day relations between masters and slaves within the household were in fact explicitly conceptualised by the masters in terms of timê (see e.g. Klees; Fisher), particularly in texts such as Xenophon’s Oeconomicus, Plato’s Laws, Aristotle’s Politics and Ps.-Aristotle’s Oeconomica. But can these dynamics of timê amount to actual relations based on mutual recognition, enabling agency, if they are instrumental to the preservation of the most extreme and brutal power relations? Or do they rather limit agency and worsen the subjugation of the slaves, tricked into concentrating their efforts towards carrying out their masters’ wishes? These issues have emerged, contentiously, also in modern work on recognition: the fundamental problem of the role of recognition dynamics in societies characterised by strongly asymmetrical power structures – of whether they are empowering or disempowering – is for instance in stark focus in the work of Louis Althusser, who coined the category of ‘ideological recognition’. Ideological recognition describes recognition dynamics that are structured in such a way as not to advance the cause of the oppressed; they rather incentivise them to buy into the existing ideological order, therefore carrying out tamely their role in the existing relations of production. The working thesis of this talk, developed and tested through engagement with literary (New Comedy), epigraphical (lead tablets and inscriptions) and historiographical (Diodorus Siculus) sources, is that as soon as a master uses honour, philotimia and the associated dynamics as motivational forces to influence the behaviour of a slave, he subjects himself to a normative order which is abstracted from his arbitrary will, which exists per se, and which can be exploited by the slave to make demands, or to develop a conscience not just of being oppressed, but of being wronged.

March 17, 2022 (Thurs): Michael Paschalis (Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of Crete)

Η απεικόνιση της σχέσης «δούλος – ελεύθερος» στο αρχαιοελληνικό ερωτικό μυθιστόρημα

Abstract

Στην πρόσφατη μελέτη του για την απεικόνιση της δουλείας στο αρχαιοελληνικό ερωτικό μυθιστόρημα, η οποία τιτλοφορείται The Representation of Slavery in the Greek Novel: Resistance and Appropriation (Λονδίνο / Νέα Υόρκη 2019), o William Owens υποστηρίζει ότι στην Καλλιρρόη, το μυθιστόρημα του Χαρίτωνα του Αφροδισιέα, η απεικόνιση της δουλείας συγκροτείται από δύο αφηγήσεις, την ρητή (explicit) και την υπόρρητη (implicit). Η δουλεία ως στοιχείο της πλοκής του μυθιστορήματος αναδύεται για πρώτη φορά, όταν ο ληστής και τυμβωρύχος Θήρων ανακαλύπτει ζωντανή στον τάφο της την πανέμορφη Καλλιρρόη, την κόρη του Ερμοκράτη, στρατηγού των Συρακουσών, και την πουλάει, στην τιμή του ενός ταλάντου, στον επιστάτη του Διονυσίου, του ισχυρού άνδρα της Μιλήτου. Σύμφωνα με τον Owens, η «ρητή αφήγηση» για το πώς ο Διονύσιος ερωτεύεται την πανέμορφη δούλη του και καταλήγει να την παντρευτεί ακολουθεί τις κατεστημένες αντιλήψεις της κοινωνικής ελίτ όσον αφορά τους δούλους και τις σχέσεις αφέντη και δούλου. Αντίθετα, η «υπόρρητη αφήγηση», που εγκιβωτίζεται σε υπαινιγμούς, αποσιωπήσεις και αντιφάσεις, αναδεικνύει την εξουσία του κυρίου πάνω στη δούλη και τον συνακόλουθο εξαναγκασμό της Καλλιρρόης σε γάμο. Κεντρικό στοιχείο της ερμηνείας του Owens αποτελεί η θέση ότι η περίοδος της δουλείας «στιγματίζει» την Καλλιρρόη, με την έννοια ότι, για να επιβιώσει, μετέρχεται «τεχνάσματα» που αντανακλούν «δουλική πανουργία» (ο όρος είναι του Χαρίτωνα), αλλά στη συνέχεια, όταν οδηγείται στην αυλή του βασιλιά Αρταξέρξη στη Βαβυλώνα για τη δίκη που θα κρίνει την τύχη της, η ηρωίδα ανακτά τη «σωφροσύνη» της και εξαγνίζεται τρόπον τινά για την προηγούμενη «δουλική» συμπεριφορά της. Ανάλογα υποστηρίζει και για τον Χαιρέα, τον σύζυγο της Καλλιρρόης, ο οποίος κατά την αναζήτησή της, αιχμαλωτίζεται και πωλείται ως δούλος στον Μιθριδάτη, τον σατράπη της Καρίας. Αντικρούοντας τις απόψεις του Owens, θα επιχειρήσω να θέσω σε νέες βάσεις τη διάκριση «δούλος – ελεύθερος» στο μυθιστόρημα του Χαρίτωνα. Θα ξεκινήσω από ορισμένες παρατηρήσεις που αφορούν την ταυτότητα και τη συμπεριφορά της Καλλιρρόης και του Χαιρέα, όπως ότι: η Καλλιρόη δεν υπήρξε ποτέ, ούτε τυπικά ούτε ουσιαστικά, «δούλη»· η πανουργία των μελών της ελίτ, δηλαδή ελεύθερων ατόμων ευγενούς καταγωγής και υψηλής κοινωνικής θέσης, είναι ασύγκριτα μεγαλύτερη από τη «δουλική πανουργία»· ο αφηγητής δεν αφήνει ούτε υποψία εμπλοκής του Χαιρέα στην απόπειρα φυγής ορισμένων δούλων του Μιθριδάτη. Γενικότερα το μυθιστόρημα ανασημασιοδοτεί την έννοια της «δουλείας», με την έννοια ότι τα μέλη της ελίτ, σε Δύση και Ανατολή, απεικονίζονται ως «δούλοι» του κάλλους της Καλλιρρόης και του έρωτά τους για αυτήν. Αυτού του είδους η «δουλεία» προτάσσεται ιεραρχικά, θεματικά και γλωσσικά της κοινωνικής δουλείας, η οποία τίθεται στην υπηρεσία της, ενώ η κοινωνική και η ερωτική «δουλεία», και η θρησκευτική λατρεία συμφύρονται, όπως προκύπτει π. χ. από τη χρήση και τη λειτουργία της «προσκύνησης». Προκύπτει έτσι μια νέα, πολύπλοκη συνάρτηση όσον αφορά τις έννοιες «δούλος» - «ελεύθερος», η οποία από τη μια ανακαλεί και από την άλλη υπερβαίνει τα παραδοσιακά σχήματα.

April 7, 2022 (Thurs): Edward Harris (Professor Emeritus of Ancient History, Durham University)

Freedom and Slavery as Political Slogans

Abstract

In 1985 K. Raaflaub published his Habilitationsschrift Die Entdeckung der Freiheit, which was later translated into English in 2004 as The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece. Raaflaub followed Finley in believing that slavery was not important in the society of the Homeric poems, was not an oppressive condition, and was only one status along a spectrum of different statuses. By the same token, freedom was not an important idea because the adjective eleutheros occurs only four times in the Iliad and Odyssey. According to Raaflaub, again following Finley, Solon only abolished debt-bondage for citizens and did not create political freedom because the people in Athens had little role in politics until the so-called reforms of Ephialtes. For Raaflaub the origin of political freedom comes during the Persian Wars when the Greeks fought against the Persian King, who was trying to enslave them. The liberty of the citizen developed only after the alleged reforms of Ephialtes when the Athenians believed that freedom was doing whatever one wanted unrestricted by limits. Though differing on a few details, the book of Orlando Patterson, Freedom in the Making of Western Culture published in 1991 follows the main outlines of Raaflaub’s analysis but goes further in claiming that women in Greece were the first to express a desire for freedom. Several advances in our understanding of Greek History during the past twenty years make it necessary to take a new look at the origins of Greek views about political freedom. First, it has now been shown (Harris 2012; Lewis 2018) that slavery was much more extensive in the Homeric poems than Finley and Raaflaub believed and that the slaves of this period were the property of their owners in the same way as slaves in later periods. The talk will show that there is already a vast chasm between freedom and slavery in the Iliad and Odyssey. Free people in this period had a concept of subjective rights, which leaders were expected to respect and protect (Pelloso 2013). Second, it has now been shown that Solon did not abolish debt-bondage but slavery for debt and also that the lawgiver established the foundations of the rule of law, which he contrasted with the slavery of tyranny (Harris 2006: 3-28, 249-70). Third, Solon and other lawgivers in this period created statutes not only for the elite, but to protect the rights of all members of the community, who had a role in approving these rules (Harris and Lewis 2022). Fourth, the so-called reforms of Ephialtes have been shown to be a myth and that the people had the main power in Athenian politics long before 462 BCE (Harris 2019, Zaccarini 2018). Fifth, the Athenian view of freedom was not “doing what one wished” but was closely related to the rule of law (Filonik 2019). Freedom under the rule of law preceded the notion of freedom of the community from foreign control and aimed at the protection of the rights of individual citizens, not simply collective decision-making. This talk will adumbrate a new approach to the development of political freedom in Ancient Greece.

Bibliography

Filonik, J. 2019. “‘Living as One Wishes in Athens: The (Anti-)Democratic Polemics,” Classical Philology 114: 1-24.

Harris, E. M. 2006. Democracy and the Rule of Law in Classical Athens. Cambridge.

Harris, E. M. 2012. “Homer, Hesiod and the ‘Origins’ of Greek Slavery,” REA 114: 345–366.

Harris, E. M. 2019. ”Aeschylus’ Eumenides, The Role of the Areopagus and Political Discourse in Attic Tragedy” in

A. Markantonatos and E. Volonaki (eds.) Poet and Orator: A Symbiotic Relationship in Democratic Athens (Berlin and Boston): 389-419.

Harris, E. M. and Lewis. D. M. 2022. “What are Early Greek Laws about? Substance and Procedure in Archaic Statutes, c. 650-450 B.C.” in J. Bernhardt and M. Canevaro (eds.) From Homer to Solon. Leiden and Boston.

Lewis, D. M. 2018. Greek Slave Systems in their Eastern Mediterranean Context, c. 800-146 B.C. Oxford.

Pelloso, C. 2013. “The Myth of the Priority of Procedure over Substance in the Light of Early Greek epos,” RDE 3: 223-75.

Raaflaub, K. 1985. Die Entdeckung der Freiheit: zur Historischen Semantik und Gesellchaftsgeschichte eines politischen Grundbegriffes der Griechen. Munich.

Raaflaub, K. 2004. The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece. Chicago.

Zaccarini, M. “The Fate of the Lawgiver: The Invention of the Reforms of Ephialtes and the Patrios Politeia,” Historia 67: 495-512.

April 14, 2022 (Thurs): Robin Osborne (Professor of Ancient History, University of Cambridge)

On Not Calling a Slave a Slave

Abstract

In modern English the word slave is tied to a particular judicial status, the status of being owned. Campaigns for the abolition of slavery were campaigns to abolish the possibility of owning another human being. We have no alternative term for those who are owned (though we can use circumlocutions like ‘servile status’), and our other terms for those performing menial tasks for others are all heard to convey that they are not owned. But ancient Greece had many terms for slaves. How were those terms used, and what is the historical implication of this multiplicity of ways of referring to slaves? This lecture explores the rich vocabulary of slavery in ancient Greece and tries to get into the mind set of those who spoke and wrote in this way.

2. Ethnicity, Race, and (the) Classics

The section “Ethnicity, Race, and (the) Classics” aims to revisit ancient (primarily, but not only, Greek and Roman) ideas and conceptions about racial and/or ethnic differentiation, based on both textual and material evidence. It equally aims to revisit the reception of such ideas and conceptions in the modern world, including current cultural practices (no less, our current debate(s) on the identity and texture of what we label as "Classics" as a scholarly field).

Programme:

February 10, 2022 (Thurs): Rebecca Futo Kennedy (Associate Professor of Classical Studies, Denison University)

Uses of Greco-Roman Antiquity in Modern Racism and Supremacisms

May 12, 2022 (Thurs): Dimitri Nakassis (Professor of Classics, University of Colorado Boulder)

The Emergence of the Hellenic Race: Greek Prehistory and Modern Scientific Racism

** POSTPONED** June 16, 2022 (Thurs): Helen Morales (Argyropoulos Professor of Hellenic Studies, University of California Santa Barbara)

Race in Aesop

June 30, 2022 (Thurs): Patrice Rankine (Professor of Classics, University of Chicago)

Oedipus in America

Abstract

Particularly as it pertains to the Black American subaltern, I am interested in modern and contemporary performances of Oedipus in the United States – primarily Sophocles’ famous titular play, but also as interpreted from Oedipus at Colonus and even such plays as Euripides’ Phoenician Women. Although the topic is potentially an unruly one, I specifically explore the modern political turn in American theater and what this means for Oedipus, broadly but more immediately the possibility of a Black American Oedipus. Knottier than the political or apolitical designation, Oedipus in America becomes an uncannily religious affair, as we see in the examples of Lee Breuer and Bob Telson’s Gospel at Colonus (1984) and Rita Dove’s Darker Face of the Earth (1996). This religious turn is at the heart of the deeper meaningfulness of Oedipus in America, the ongoing work of myth to grapple with the fateful problems implicit in the original Sophoclean performance.